Introduction

The discussion here is direct and to the point. Please understand it's the intent of the Author to get your attention to help you.

Working with receiver testing

Due to the inability of certain people to communicate properly and understand all the aspects of site testing this page was created to read, compare notes and build on for the benefit of all. Human communication, comprehension and understanding problems is beyond the scope of this document. However, the reader should keep these problems in mind when dealing with site issues and interfacing with other companies and government Agencies. Misinformation, misunderstandings, lack of proper training and/or experience, bogus readings, log entries, technician and management diagnostics and plan of actions for problem solving are commonly mis-directed with considerable time and expense wasted in the wrong direction of efforts. This can lead to the general desensitization (pun intended) and poor attitude of the workforce in most any private company or government in the technical (repair) field around this country. Fortunately, there still is a handful of RF technicians that care to understand what the problem is and the proper way to solve, or at least, reduce the symptoms to an acceptable figure. If you are reading this it's most like you are in one of the latter. This is a good thing.

While past 2-way industry uses the "watts" figure, competent companies, such as Motorola provide supplemental training to LMR technicians in better practices and methods to perform their jobs, by forgetting the "watts" and "volts" figures and work with logarithmic figures instead. This philosophy will be realized in this entire document. One other note that this document has antenna gain (and some other types) figures are sometimes rounded off to the nearest dB for ease of calculations for readers only for educational reasons. Obviously, real field figures could have fractional amounts.

The Author's been using the procedures/tests here, since 1978, both professionally and non-professionally. The latter is for amateur radio; where repeater owners try to get the best possible performance out of a station. In the professional world we call this station "optimization". These procedures can be used for any LMR type of service. These are for a standard, stand-alone VHF repeater, closed spaced between the transmitter (output) and receiver (input) frequencies.

Keep in mind the transmitter is running in the neighborhood of +50 dbm, while its receiver is trying to listen to a signal in the neighborhood of Ė117 dbm, while on the same antenna. (167 dB difference). While other bands (6, 1.25, . 7 meter, etc.) (theory is the same) many amateur repeater owners have problems on the 2-meter band therefore, the examples will be focused on that. The Motorola Quantar base/repeater unit will be the prime example for equipment covered in this article however, this practice can apply to any 2-way brand and model of equipment. The transmitter Tx power out is rated at +50 dbm, so if your station is different take that into consideration when evaluating performance.

Procedures

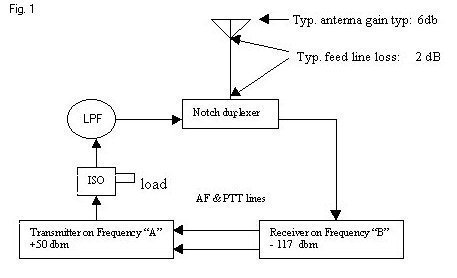

Figure 1 shows a basic station. Normally, you'd have a transmitter-receiver unit, typically in the same chassis, with (proper length) cables connecting to a 3-port device, called a duplexer; with the common port connected to the antenna. Shown here is a basic band-reject for this study. It's shown only for a simple example. More commonly is the pass/reject type duplexer, for the advantage of additional filtering outside the repeater's frequencies and normally a slight increase in insertion losses however, gaining in system performance. Since the price tag is still manageable for the latter type, its recommended to use this type for all sites with other stations nearby. Many site owners require this type of band-pass protection as well.

Typical feed line loss is 2 dB, while the typical antennas used today are around 6 dB gain. Also shown is the optional isolator, with its associated low pass filter. This filter is mandatory for proper isolator operation, especially if there are other stations at the site. For the Motorola Quantar having a single stage isolator built-in the unit, its unknown (at this time) if there's also a LPF built-in as well. If not, signals can penetrate the isolator and do more harm than good. There are details about this on a separate document on SRG's web site

Perhaps some basic theory on the isolator is in order: This device normally is tuned in two directions, forward and reverse (reflected) on the same transmitter's frequency. RF power will easily run through the device in the direction of the antenna, while RF in the reverse direction is re-routed to the 3rd port, with a termination. The circular arrow indicates this, hence a "circulator". With the addition of the termination on the 3rd port the device now carries this name. Its almost semantics, between "isolator" and "circulator". While looking at the path from the antenna to the termination its important it will handle enough power anticipated, including the stationís own transmitter, in the case of a broken antenna, thus, a bad return loss figure. (Reflected power coming back from the line/ant fault) This can protect the transmitter.

Occasionally, another scenario happens. If a nearby adjacent transmitter's power is coming down the line, so close in frequency any band pass cavity won't filter it out, the reverse direction of the isolator can be tuned to that neighbor's frequency (instead of your own transmitter's frequency) to route that (offending) power to the termination as well. The drawback is that your own transmitter may not be protected. To overcome this you can install two isolators; one on each frequency however, at the cost of additional insertion loss.

In either case, routing return loss (and other signals) to the termination greatly reduces the chance of an IM mix in your station transmitter output section, the power amplifier. Power amplifiers for 2-way F.M. are usually type class C, which is a opportune mixing point for two or more signals to produce "other" unwanted (interfering) signals.

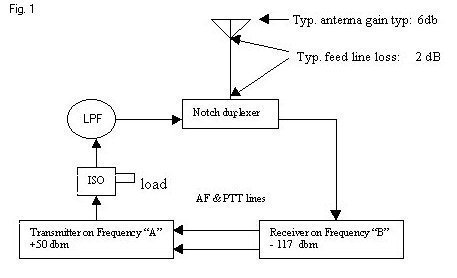

The Motorola Quantar base receiver is "stagger" tuned in the RF front end, from the factory. This is to accommodate a multi-frequency base station. Single frequency operation can realize increase performance if the front end is retuned for a single RF peak. This may also help in adjacent channel degradation from other stations at the site. In some cases, where a site is "hostile" (in RF terms) a band pass cavity can be added on the receive side to further enhance filtering as shown in figure 2. This of course, does not come without a price, usually in the form of 1-3 dB receiver (insertion) loss of sensitivity. However, if this cavity improves the over-all performance by filtering out adjacent signals, then it will be a system gain in performance. (reduction in desense minus I.L.= increase in system performance).

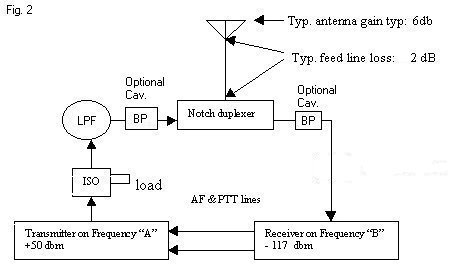

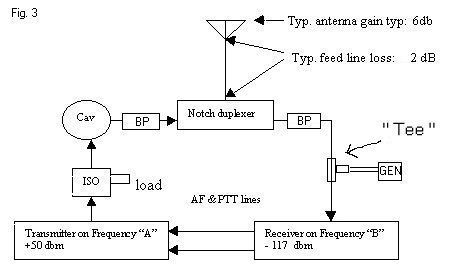

To test the system performance (repeater and/or base station's sensitivity) you can perform the following tests as (partially) shown in figure 3. Two test are involved, one, site (noise) degradation, and, two, repeater degradation (Tx-Rx). Both tests check desense of the stationís receiver. Each test must be performed separately to properly evaluate and document the stationís performance and find possible solutions to a problem.

This cannot be stressed enough.

First, connect any good quality signal generator in line with the station with an "iso-tee". This device has a throughput path, plus an isolated third port. The reason is not to load, or affect the line impedance or other variables, plus to protect the signal generator from the high power of the transmitter(s). True, a quick "spray" method can be used, by a little whip antenna on the signal generator however, this induces propagation variables and should be only used as a last resort, or a rough measurement. For this exercise we do not recognize this "spray" method. Continuing, the "safest" point to install this device is on the receiver side, to prevent a mixing variable with high power levels as in the case of a site shared with broadcast stations. Optionally, you can add a 6-db pad in line with the generator (with the offset level to figure in, of course).

Test # 1: SITE NOISE

Step 1: Connect an "Iso-T" in the receiver line, with the third port connected to the RF signal generator.

Step: 2: Terminate the antenna port of the duplexer with a load.

Step 3: Measure and log the signal generator level to produce a receiver indication.

NOTE: This can be squelch break point, 20 dB quieting, or 12-dB sinad. Any method is satisfactory, however, the same method must be used for the entire test(s) to be accurate. There will be considerable isolation with the "T", so your signal general levels will be rather high; typically, Ė50 dbm or better. The absolute level you'll need to do this is not important. What is important is the relative change in signal general levels (in log) that you will be logging (no pun) in the next steps.

Step 4: Connect the antenna port of the duplexer to the outside antenna.

Step: 5: If there is a change in the receiver, adjust the signal generator level to produce the same receiver indication as discussed, above. This normally will be an increase in the generator level. Log this measurement.

Step 6: The difference between the generator levels in step 3 and 5 is your site noise, or site receiver degradation in the from of desense. O would be great; typical is 4 dB.

NOTE: Some telecomm technicians also call this "dynamic sensitivity" by the difference between the (laboratory) spec sensitivity from the dynamic sensitivity that you find. Another name used by telecomm companies is "E.R.S." meaning Effective Receiver Sensitivity.

Test # 2: REPEATER DESENSE

NOTE: This test is for repeaters only. If you are running a simplex base station (T-R relay, etc.) then this test does not apply.

Step 1: Terminate the duplexer antenna port with a load capable of handling the transmitter's power level of +50 dbm. That's 100 RF watts (at 50 ohms) for math challenged people.

Step 2: Measure and log the signal generator level to produce a receiver indication. (as in the previous test, step 3). Leave the generator on.

Step 3: Key up the repeater's transmitter. If there is a change in the receiver, adjust the signal generator level to produce the same receiver indication. De-key the transmitter and log this measurement.

Step 4: The difference between the signal generator levels of step 2 and 3 is your repeater desense (Tx-Rx) on a dummy load (termination). This normally should be zero if the stationís equipment is properly configured and tuned.

Step 5: Connect the antenna to the proper port on the duplexer.

Step 6: This is the important part; If you performed the site noise check (test 1) your signal generator level may need to be increased to produce that same receiver indication as in the last part of step 5, test 1. Again, leave the generator on.

Step 7: Key the repeater's transmitter. Adjust the signal generator level to produce the same receiver's indication. This usually is an increase in the signal generator's level. Typical is 1-2 db. Log this measurement.

Step 8: This is the repeater (receiver) desense on the antenna. Its very important to understand this figure. (This is not site-only noise).

Step 9: Add the desense in Test 1, step 6, to Test 2, step 8. This is your total operational (dynamic) system degradation, in the form of two types of desense;

SITE and REPEATER (transmitter) desense. To be clear, this is your receiver degradation, before you do anything else.

Period.

For the full picture of an LMR (2-way radio) station, here's an example:

For sake of understanding we will use the figures of 4 dB for site noise and 4 for repeater desense. That's an 8 dB decrease from the static receiver sensitivity of Ė117 dbm = Ė109 dbm. This would be considered a poor to fair performance. However, there's more to consider and to remember that you are working with negative numbers in most of the receiver figures. Also, we should consider all that's happening with the station's RF levels.

For the 2-way industry, typical figures at a hostile site are:

Repeater transmitterís power out: +50 dbm

Repeater receiverís (static) sensitivity: -117 dbm (for 12 dB SINAD)

Repeaterís Tx isolator insertion loss: 2 dB

Repeaterís Rx band pass cavity loss: 2 dB

Repeaterís duplexer loss: 2 dB (thatís about on 1.5 db the Tx and 1.5 db Rx side; rough-average)

Feed line loss: 2 dB

Antenna gain (over a 1/2-wave dipole): 6 dB

At this point the antenna gain makes up all the station losses. *Remember, you don't care about the losses at this point. Therefore, the effective receiver sensitivity is still -117. Now, lets throw in the real world:

Typical site noise (desense) 4 dB

Typical duplexer desense on a dummy load 0 dB

Typical duplexer desense on the antenna 4 dB

Rx sensitivity, plus all other losses = dynamic system sensitivity:

-117

- 2

- 2

- 2

+ 6

- 4

- 4

+_____________

= -109 dbm sensitivity (poor-fair)

This case shows a poor operation however, this is not uncommon at RF hostile sites with high-power broadcast stations nearby. You can build on these (poor) figures to improve (optimize) your station. The Author likes to achieve in the -110 ~ -115 dbm area for the SRG sites.

Station optimization can be realized if the technician understands what's happening. For example, the 6 db gain antenna is calculated to "help" the receiver's performance. However, in some cases more antenna gain makes more desense (taking in more interference), thus, a lower gain antenna may be a "wash" with the final receiver's performance, with the advantage of lower cost and lower ice loading issues. On the other hand, more antenna gain will help with the station's ERP (Tx)(only) causing better reception on the subscriber end.

A last word about locating the desense; Normally, if and when you have the problem at a communications site the owner could will provide you with a list of your "neighbors" at the site (yea, right, har, har). Should that person not have the information, or you are otherwise on your own, you still have a few options. They are normally two types of interference, in the form of receiver desense, and that is, continuous, which could be from general noise from any electrical device including thermostats, fluorescent lights or networking equipment. In one case, the Author found a digital microwave radio had a "burdi" causing interference on one of the LMR stations at the same site. The other is from intermittent interference, because you can hear the quieting changes while performing the site noise test. Both are possible to cure with enough persistence. Here's some tips:

While performing the previous tests use a (separate) spectrum analyzer and watch for signals coming up while the problem exists. This is for the second type (intermittent) when a neighbor's transmitter comes on for a few seconds. Possibly, a dispatch simplex remote base or a repeater. Most commercial and public service/government repeaters have short tails. That's your first clue. Some amateur repeaters have longer tails. Amateur packet stations running AX-25 protocol have very short transmissions around a second sometimes. The constant "noise" in the form of site desense (first type) is harder to find. Here's a way to accomplish this:

Build up a portable "station". This will consist of a "station" antenna and a way to mount it to the ground in the form of a tripod. Then you'll need a signal generator, an iso-"tee", some connectors, coax and a "test" receiver. For this experiment the Author used a "portable" signal generator and a home built tripod, with a quick release antenna mount, for grabbing and walking around the suspect area of interference. The test receiver is an Icom IC-2AT. You can substitute a 3AT or 4AT depending on which band you are working with. These portable radios have a poor rejection front end so will be good in a worse case senerio. In case your desense is overwhelming, there are commercial receivers that can be crystaled or programmed on the frequency of interference. Put it all together in a single unit, powered by a couple of 6 volt lantern batteries to obtain a 12v source. Shown here is the complete unit, with a back pack to carry the sig. gen. battery, and other cables.

A nice touch is use of the chest pack to carry the portable "receiver" with its own spare battery. On the right shows a quick and handy way to pull off the antenna of the tri-pod for easy "walk-around" a suspect area. For this project the Author used a gain antenna. You don't have to; you can use a unity, such as a 1/4 wave ground plane type. If you do this, keep in mind the pattern on a 1/4 wave has a high lift-off (the donut) so most of the desense "sniffing" (pattern) area will be above you. If you are anal, the best antenna to use for this project would be a unity 1/2 wave folded dipole, center feed.

Here's a close up of the antenna and iso tee setup; just a few mixed connectors held with a couple of hose clamps. The "tee" is made up from a normal Tee with the center pin removed. That will give around 40 db of isolation from the sig. gen. to the receiver. You may want to carry a 50 ohm termination with the quick-release UHF connector to check site noise at the location you might have found the source of the noise for an accurate measurement. In place of the home-made tee there are commercially made ones as well.

Another note: "UHF" connectors are not high performance and flooded the LMR market since the 1960's. A much better type is N or BNC however, for this project a UHF connector system should be fine. Unless you suspect the other "cheap" methods such as the hose clamps, are contributing to the problem this setup will get you pointed in the right direction.

Back to SRG tech page This document may be distributed with the permission of the Author and he given credit of this document. ![[SRG home Direction]](images/srghome.gif)